Shape memory alloys are a fit with textile technologies.

by Janet Preus

What makes a material robotic? According to Brad Holschuh, Ph.D., assistant professor of wearable technology and apparel design in the College of Design at the University of Minnesota (UMN), the simplest explanation is that it’s a synthetic product with mechanical actuation that can move or complete actions independent of, or in partnership with, humans.

“Soft roboticists say the true defining feature is mechanical capability—the ability to create movement, force, displacement, torque, pressure, stroke—all the hallmarks of a typical mechanical system, but using materials that are nonrigid,” he says.

At IFAI’s 2019 Smart Fabrics Virtual Summit, Holschuh, who co-directs the UMN Wearable Technology Laboratory (WTL), gave a presentation titled “Soft-Robotic Textiles Using Integrated Active Materials.” He noted the many materials and their capabilities that can be useful in soft robotic applications, particularly in shape memory functions. Holschuh says that because shape memory alloys (SMAs) “can change shape, and the change can be controlled in a way that is reliable and repeatable,” they can be useful in a variety of applications and markets.

One application is in compression garments, which are widely used and have been around for quite a while. “But I’ve never met a single person that says they enjoy wearing a compression garment that’s on the market,” Holschuh says. “The two biggest complaints are that they’re really hard to put on, and once they’re on, they squeeze you all the time.” It’s also “a relatively simplistic therapy. It’s not dynamic; it’s just there.”

Problems with existing compression garments are exacerbated when used by people who are infirm or have difficulty putting on and taking off the garment. “The alternative is a pneumatic technology,” he says, “which can offer a degree of controllability, but pneumatic compression garments usually require that the person is stationary.”

On-body actuation

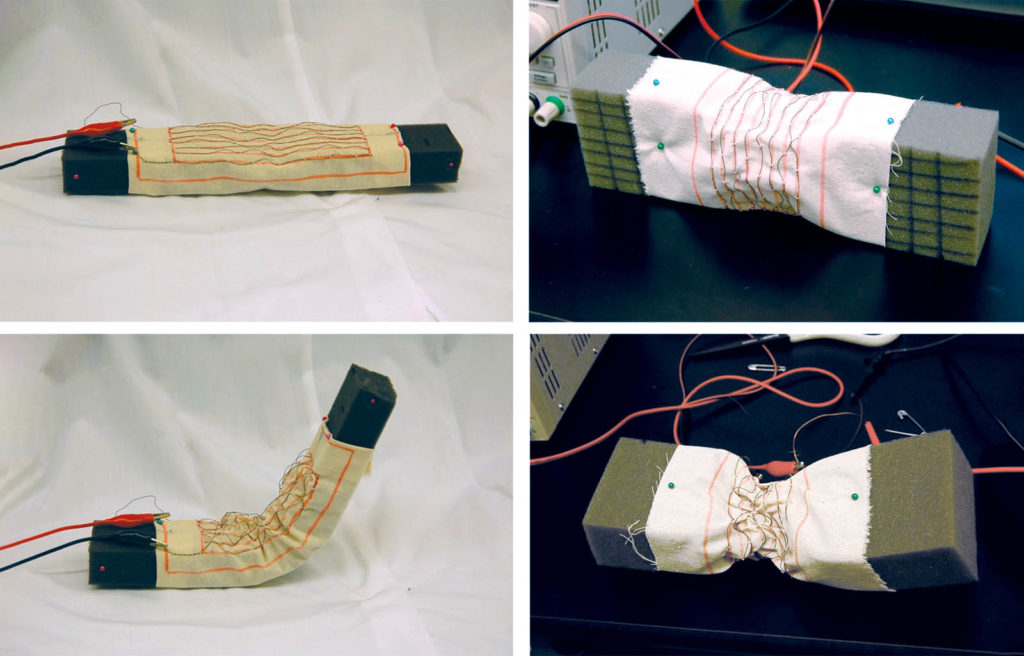

Holschuh’s work has moved beyond both types and incorporates on-body actuation. “What we designed is compression garments that give you the control of a pneumatic, but give you the form factor that’s much more in line with what you can wear in your everyday life.” In order to do that, Holschuh and his team had to address two main issues with SMAs: they take a lot of power, and they generate heat—too much heat.

His team has been able to bring temperature thresholds down and close to body temperature, so that simple contact with the body will activate the function, “or a little higher than body temperature, so the battery can be smaller,” Holschuh says.

Because these devices could use the body’s own energy without any other power source, an active panel could be taken out of a freezer and put into an article of clothing, such as leggings. As soon as it’s worn, it would respond to the wearer’s own body heat and activate the functionality. The same concept could provide “smart braces” for teeth that would tighten in response to the heat that occurs naturally in the wearer’s mouth.

Holschuh is currently working with Rachael Granberry, a Ph.D. student and NASA Space Technology Research Fellow, on a NASA project designing customizable compression garments for astronauts. When astronauts return to Earth, they need an effective lower-body compression garment to mitigate the effects of weightlessness on their circulation. Compression stockings identical to those we use on Earth are currently in use by NASA, but the stockings can’t be worn for long periods of time, so if the astronauts’ re-entry is delayed, there’s a problem. Work at the WTL has been focusing on a controllable garment to respond to individual needs and changes in circumstances.

The team’s work could someday translate to products for treating conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and autism in children, where compression garments have been found to be an effective treatment. In both cases, the technology can create haptic stimulation on the body that mitigates anxiety and stress for a wearer who might otherwise be agitated.

New technology is “on the cusp of having truly interesting use in wearable situations,” says Holschuh, including in products that users won’t mind wearing. A remotely controlled compression vest WTL developed, for example, “can create compression dynamically and strategically when and where you want, and nobody else will know that this is happening.”

Knitted structures can be used to create two-dimensional motion (both expansion and contraction) to customize a wearable compression device with actuators that can be activated individually or in varying groups. Furthermore, it’s possible to amplify the haptic experience if the actuators are put in a braided structure, he says.

Collaborative work

Regardless of the nature of the project, or the type of technology employed, Holschuh says developing wearable solutions needs to have a collaborative approach, particularly to engage apparel designers who understand how to make products truly “wearable.”

“Right now we have 12 grad students; half are apparel designers and the other half are engineers. You can’t propose to make a wearable system if you don’t get the skills that are centuries old in apparel design.”

Holschuh says that when he worked in the aerospace department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), “I couldn’t find anybody with apparel expertise at the time. Then you end up with engineers who can barely work sewing machines. It doesn’t begin to incorporate what clothing designers know.”

He says he feels fortunate to have landed at UMN where they have people with this expertise. “There’s extreme potential for these problems to be solved if you bring these communities together. Now I live in a world where you have this blending of backgrounds.”

He says that clothing is a system, too, and can be approached just as an engineer would. “Functionality comes first for most, but wearability is a function.”

Work elsewhere

Holschuh notes several other institutions doing interesting work with integrated active materials. The University of Texas at Dallas (UT-Dallas) has used ordinary materials such as nylon fishing line to create “artificial muscles.” That work was published in Science in 2014, and the work is ongoing.

MIT has used nylon fibers made to flex like muscles and, in a partnership between Purdue and Yale Universities funded by NASA, has developed SMA robotic fabric that’s wrapped over soft structures to create two- or three-dimensional structures. Holschuh’s colleagues at UMN, Julianna Abel and others, are developing active knit actuation, and Harvard Biodesign Lab is also working on mechanical actuation and soft robotics.

With a range of markets that could use these types of technologies, it’s understandable that many researchers are working on them. Possible uses include a new approach to tourniquets that may result in a “skin suit” for soldiers, with embedded technology that enables the clothing to respond to an injury when a medic is not on hand.

Applying these technologies to the progressive treatment for spine correction, for example, or even healing broken bones could change how these conditions are treated. Research on exoskeletons to support mobility is also underway.

Other possibilities include “smarter” spacesuits for astronauts, easy-to-control consumer shapewear, and garments with changeable lift and drag properties for competitive athletes. “The goal of our research program is to have a future where clothing can change without a motor,” Holschuh says.

Janet Preus is senior editor of Advanced Textiles Source. She can be reached at jlpreus@ifai.com.

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG